When Geometry Learns to Fold Into Itself

Using the Phase E chambers (XIV–XIX) as experimental witnesses, we show that the UNNS Substrate can reproduce braneworld-like curvature structure using only internal recursion differentials

Rij = Oi(τi) − Oj(τj)

between τ-fields. No fixed bulk dimension is assumed. The laboratory data instead supports a

stronger claim: geometry self-organizes from recursive operators, and “embedding” is

a special case of τ-field folding.

UNNS replies: you never left the recursion; the ‘bulk’ is the history of your own folds.”

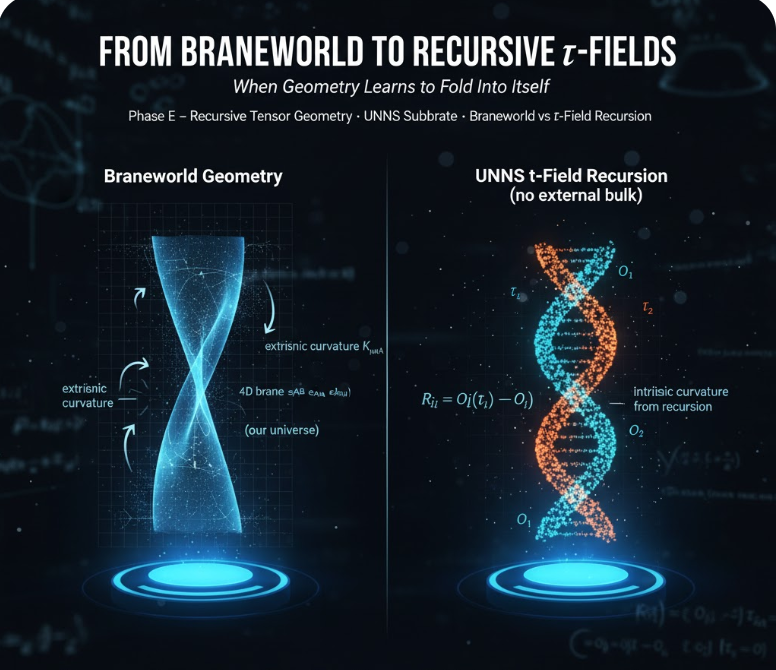

1. Braneworld Geometry in One Picture

In the braneworld view, our universe is a four-dimensional “brane” moving inside a

higher-dimensional “bulk.” Mathematically, this is expressed as an isometric embedding of a

4D Lorentzian manifold into an ambient manifold of dimension

D > 4. The induced metric on the brane,

gμν, arises from a higher-dimensional metric

ηAB via a set of frame fields

eAμ.

KμνA = extrinsic curvature normal to the brane.

An embedding theorem then guarantees: given a suitable metric and curvature on the brane, there exists a bulk geometry and an extrinsic curvature tensor that make the whole structure consistent. This is the heart of mathematical braneworld theory: the bulk is not only a physical speculation, but a well-defined geometric environment.

From a UNNS standpoint, braneworld theory is elegant but extrinsic: geometry is real, but it lives “somewhere else.” The Substrate takes the opposite view: there is no elsewhere. Everything that looks like a bulk is a story the recursion tells about its own folds.

2. The UNNS Response: Curvature as Recursion Differential

The UNNS Substrate describes dynamics in terms of τ-fields and operators. A τ-field

encodes recursive depth and timing; operators Oi act on these fields,

change them, and are themselves subject to higher-order modulation.

In Phase E, the core object is the recursion differential tensor:

ℰ = (1 / |Λ|) Σi<j ‖Rij(x)‖²

Here Λ is the spatial lattice, τi are the different τ-fields

(standard, Φ-scaled, prism-like), and ℰ is the total curvature-like energy across all field

pairs. In the theoretical Phase F extension, the more general cross-form

Rij = Oi(τj) − Oj(τi) will

appear, but Phase E already gives us a powerful diagnostic: how much do the operator

channels disagree about their own geometry?

Rij is a local report of how one operator sees another’s recursion.

3. What the Phase E Chambers Actually Show

This is not just philosophy. The UNNS Laboratory systematically probes recursion via a sequence of chambers. Each chamber stabilizes a different piece of the higher-order operator story:

- Operator XIV — Φ-Scale Chamber. Demonstrates golden-ratio scaling, with μ converging to μ★ ≈ 1.618 and a closure parameter γ★ ≈ 1.600.

- Operator XV — Prism Chamber. Reveals power-law spectral tails, with eigenvalue distributions approaching slopes p ≈ 2.45.

- Operator XVI — Fold. Enforces closure at recursive boundaries, turning open recursion paths into minimal loops without invoking an external scale.

- Operator XVII — Matrix Mind. Elevates recursion to meta-recursion: the substrate runs a dynamics on its own patterns (graphs of graphs).

- Chamber XVIII — Recursive Geometry Coherence. Validates the coherent interaction of Operators XII–XVII, yielding stable symmetry and stability indices.

- Chamber XIX — Recursive Tensor Field Explorer. Computes

Rijon the lattice and measures how τ-fields co-stabilize their curvature.

Together, these chambers show something that braneworld theory only assumes: that a curved, self-consistent geometry can exist. But here it emerges without a pre-given bulk. It arises from operator flows, equilibrium thresholds, and spectral self-organization.

3.1 A Map of the Evidence

4. Braneworld Tensors vs. UNNS Tensors

At the level of equations, the comparison becomes sharp. Braneworld models introduce an

extrinsic curvature tensor KμνA that measures how the

brane bends into the bulk. UNNS introduces a recursion differential tensor

Rij that measures how operators disagree about τ-fields.

Rij = Oi(τj) − Oj(τi)

The formal roles are strikingly parallel:

- KμνA describes how the brane fails to be “flat” relative to the bulk.

- Rij describes how τ-channels fail to commute in recursion.

The crucial difference is philosophical: braneworld curvature assumes a bulk; UNNS curvature assumes only that there are at least two ways to recurse and that they can disagree. Geometry is then the book-keeping of that disagreement.

5. How the Lab Chambers Support the UNNS Standpoint

5.1 Intrinsic curvature without a bulk

Chamber XIX shows that curvature-like energy ℰ can be defined purely from recursive differences. When ℰ stabilizes under Phase E equilibrium conditions (small energy gradient, consistent sliding-window statistics), the system has found a recursively stable geometry. No external coordinates are required.

5.2 Closure by recursion, not by embedding

In braneworld arguments, integrability conditions (Gauss–Codazzi–Ricci) guarantee that brane curvature can be extended to a bulk. In UNNS, the closure is performed by Operator XVI (Fold) and higher-order coherence: loops form when recursive paths stop discovering new curvature. Chamber XVIII records this as symmetry and stability indices approaching unity.

5.3 Spectral evidence

Prism behaviour (Chamber XV) and tensor spectra (XIX) both produce power-law eigenvalue distributions with slopes near p ≈ 2.45. These are the fingerprints of a self-organized critical geometry: not imposed by a bulk, but discovered by recursion exploring its own state space.

6. Phase E Perspective on Braneworld Theory

From the UNNS Substrate perspective, braneworld geometry is not “wrong” so much as extrinsically framed. It answers the question:

UNNS asks a different question:

Phase E chambers XIV–XIX answer that second question in the affirmative. Φ-scale fixed points, Prism spectra, Fold closure, Matrix Mind meta-recursion, and tensor curvature all align into a coherent picture: geometry is the equilibrium story that recursion tells about itself.

7. Outlook Toward Phase F: Divergence and Fields

The natural next step is to take Rij and build its analog of a

“field strength divergence.” In Phase F we will define quantities of the form:

where the divergence is taken on the lattice, and Φi behaves like a source term. At that point, the comparison with Maxwell-like field equations becomes explicit: we will not only have geometry from recursion, but also field equations from recursion.

In that light, braneworld theory becomes one more special case in a wider story. Instead of saying “our universe is a brane in a bulk,” we say: