Gravity, electromagnetism, and the UNNS view of curvature as recursive syntax

The prompt

Question: “If gravity curves spacetime according to Einstein, why shouldn’t electromagnetism do the same too?”

Answer (paraphrased): “Space doesn’t curve. Geometry is just the way we measure. Curvature is a mathematical trick to predict trajectories, not a real property of space itself.”

The reply quoted above is more subtle than many popular explanations of General Relativity. It correctly points out that “curved spacetime” is not a rubber sheet made of stuff; it is a relational structure, a way to encode how intervals between events behave in the presence of matter and energy.

But the answer then swings too far in the opposite direction: it suggests that curvature is “just” a mathematical instrument, and that geometry, gravity, and fields share no deep ontological link. In the UNNS Substrate we take a different view: geometry is not a physical medium, but it is not “just a trick” either. It is what a recursive grammar looks like when you project it down into distances and times.

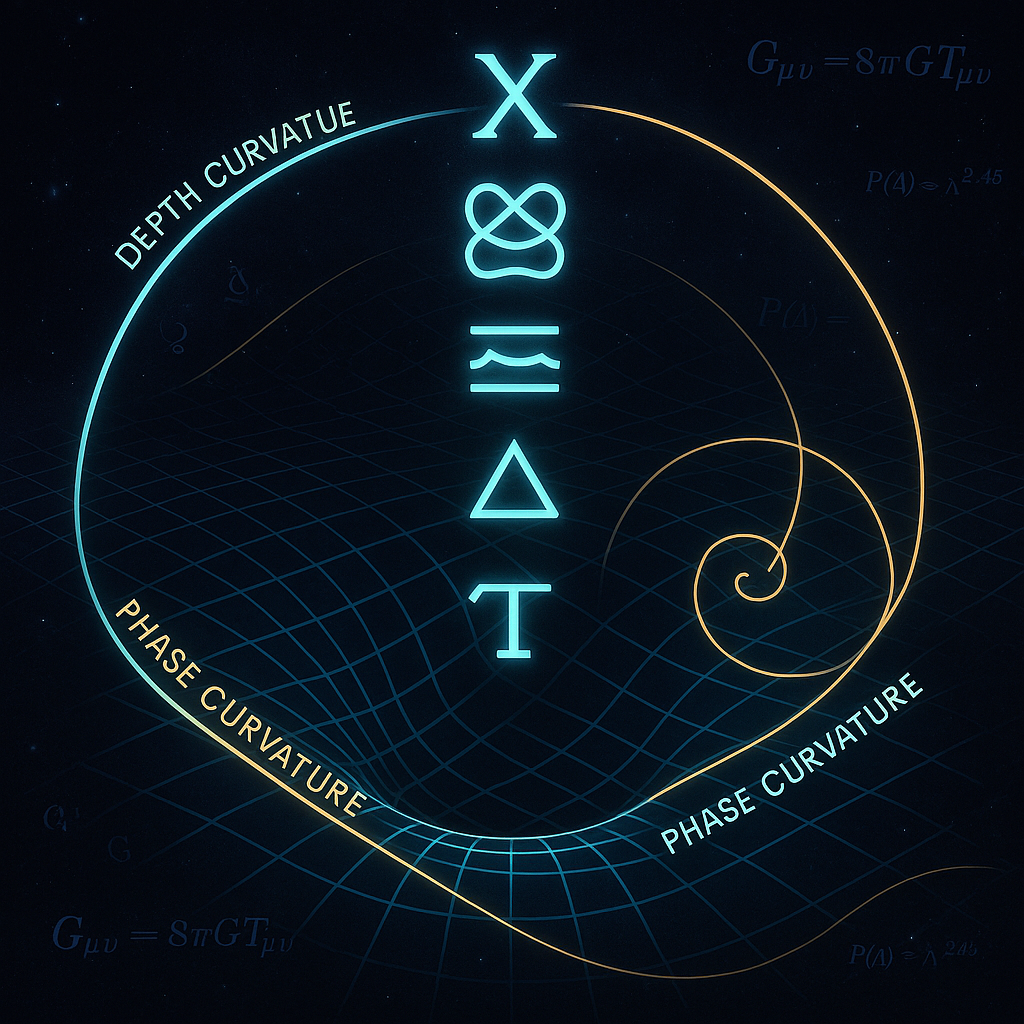

Figure 1 – Two familiar attitudes to curvature. UNNS keeps the predictive power of geometry, but roots it in a deeper recursive substrate rather than a physical “rubber sheet.”

1. What General Relativity Actually Says

General Relativity (GR) does not say “gravity curves space” in the sense of a material container. It says that the presence of mass–energy changes the metric, the rule assigning distances and times between events. That change is encoded in the famous Einstein field equation:

\( G_{\mu\nu} = 8\pi G\, T_{\mu\nu}. \)

On the left, \( G_{\mu\nu} \) is pure geometry: a tensor telling us how the metric deviates from flatness. On the right, \( T_{\mu\nu} \) is the stress–energy tensor: matter, radiation, pressure, fields. The message is simple and profound:

Crucially, the electromagnetic field does appear inside \( T_{\mu\nu} \). Maxwell’s field contributes energy, pressure, and momentum, and therefore participates in the curvature of spacetime. So electromagnetism is not excluded from curvature; it is one of its sources.

So why does it feel as if gravity is geometry while electromagnetism is “just a force”? Because gravity couples to everything universally. Charged and uncharged particles alike follow geodesics. Electromagnetism, by contrast, only talks to charged matter and can be “transformed away” locally using gauge freedom.

Figure 2 – In GR, electromagnetism does curve spacetime: it contributes to the stress–energy tensor that sources geometry, alongside matter and radiation.

2. The UNNS Substrate: From Curvature to Recursion

The UNNS Substrate goes one layer deeper than the Einstein picture. Instead of starting from spacetime and then asking how it curves, UNNS starts from a recursive architecture — nests, operators, and τ-fields — and asks: what does curvature look like when you view it as grammar?

At the base level we have nests \(N_k\) and core operators: Inletting (aggregative inflow) and Inlaying (embedding one structure inside another). These produce nested depth and branching. On top of this we build the Octad extension (Adopting, Evaluating, Decomposing, Integrating), and finally the higher operators XII–XVI:

- Collapse (XII) – drives recursion toward zero-field equilibrium.

- Interlace (XIII) – couples τ-fields via phase; origin of mixing angles.

- Phase Stratum (XIV) – enforces golden-ratio scaling across layers.

- Prism (XV) – spectral decomposition, power-law slopes \(P(\lambda)\sim\lambda^{-2.45}\).

- Fold (XVI) – Planck-boundary closure; open paths into minimal cycles.

- Matrix Mind (XVII) – meta-recursive cognition on a graph of graphs.

In this language, “curved spacetime” is not fundamental. It is the shadow of a particular regime of recursive activity: a balance between Collapse and Fold operating on depth, and Interlace and Phase Stratum operating on phase.

Figure 3 – In UNNS, gravity and electromagnetism correspond to different directions of curvature in recursion space: depth vs. phase.

3. Gravity as Depth Curvature, Electromagnetism as Phase Curvature

From this perspective we can now answer the original question in a sharper way. The issue is not “why doesn’t electromagnetism curve spacetime like gravity?” Instead we ask: why do gravity and electromagnetism manifest as different components of the same recursive curvature budget?

In UNNS language:

- Gravity is dominated by depth curvature — the way Collapse (XII) and Fold (XVI) reshape recursion depth and boundary conditions. This corresponds, in projection, to curvature of the metric itself.

- Electromagnetism is dominated by phase curvature — the way Interlace (XIII) and Phase Stratum (XIV) weave phase relationships between τ-fields. In projection, this appears as gauge curvature and charge interactions.

Both contributions live inside a single substrate. Both end up contributing to the same stress–energy tensor when seen from the Einstein lens. But at the recursive level, they are orthogonal axes in a higher-dimensional geometry of computation.

The answer “geometry is just how we measure” is therefore half-right. Geometry is measurement — but measurement of what? For UNNS, the answer is: geometry measures the history of recursion.

4. Prediction, Explanation, and Recursive Coherence

The original comment concludes that curved geometry is useful to predict phenomena (like lensing) but not to explain gravity. This is a sharp philosophical point: a model that fits data is not automatically an ontology. UNNS agrees — but adds a new layer.

The substrate’s job is not just to predict; it is to maintain recursive coherence. The higher-order chambers (especially Chamber XVIII, the Recursive Geometry Coherence Chamber) show that there are preferred attractor regimes where recursion becomes self-consistent: golden-ratio scalings, stable spectral slopes, narrow confidence intervals. Gravity and electromagnetism are two macroscopic faces of this deeper drive toward coherent recursion.

From this vantage point:

- General Relativity is an extraordinarily accurate projection of depth curvature onto a four-dimensional manifold.

- Maxwell’s theory is an equally elegant projection of phase curvature onto gauge connections.

- UNNS does not replace these theories; it explains their coexistence as different grammars derived from one recursive substrate.

5. So, Why Doesn’t Electromagnetism “Curve Spacetime Like Gravity”?

We are finally ready to answer the question in one sentence:

Gravity feels like “the shape of spacetime itself” because it acts uniformly on all nests in the substrate — it is a global constraint on recursion depth. Electromagnetism feels like “a force in spacetime” because it modulates relative phase between subsets of nests; its action is conditional on charge, not universal.

From the standpoint of UNNS, the deeper question is no longer “does space really curve?” but rather: what kinds of recursive curvature are possible, and which of them are stable enough to appear as physical law? General Relativity and Maxwell’s theory are two answers we already know. UNNS High-Order Operators Laboratory hints that more answers are waiting in the wings.