Quantum Tunneling as Sobtra Dynamics

What classical physics forbids, quantum mechanics allows. In the UNNS substrate, this “impossibility” becomes a clean structural rule: tunneling happens when Collapse chooses the sobtra channel instead of sobra.

1. Classical vs Quantum: The Textbook Story

The usual textbook explanation looks like this:

- A particle sits in a valley (a potential well).

- There is a hill (energy barrier) between the valley and a lower valley.

- Classically, if the particle does not have enough energy to climb over the hill, it stays forever.

- Quantum mechanically, the wavefunction has a “tail” under the hill, and the particle can tunnel to the other side with some probability.

From a classical point of view this looks like a miracle: the particle appears where it “should not” be. Quantum mechanics formalizes the miracle with amplitudes and barriers. UNNS goes one step further and asks:

What actually happens to the residual structure of the system during Collapse?

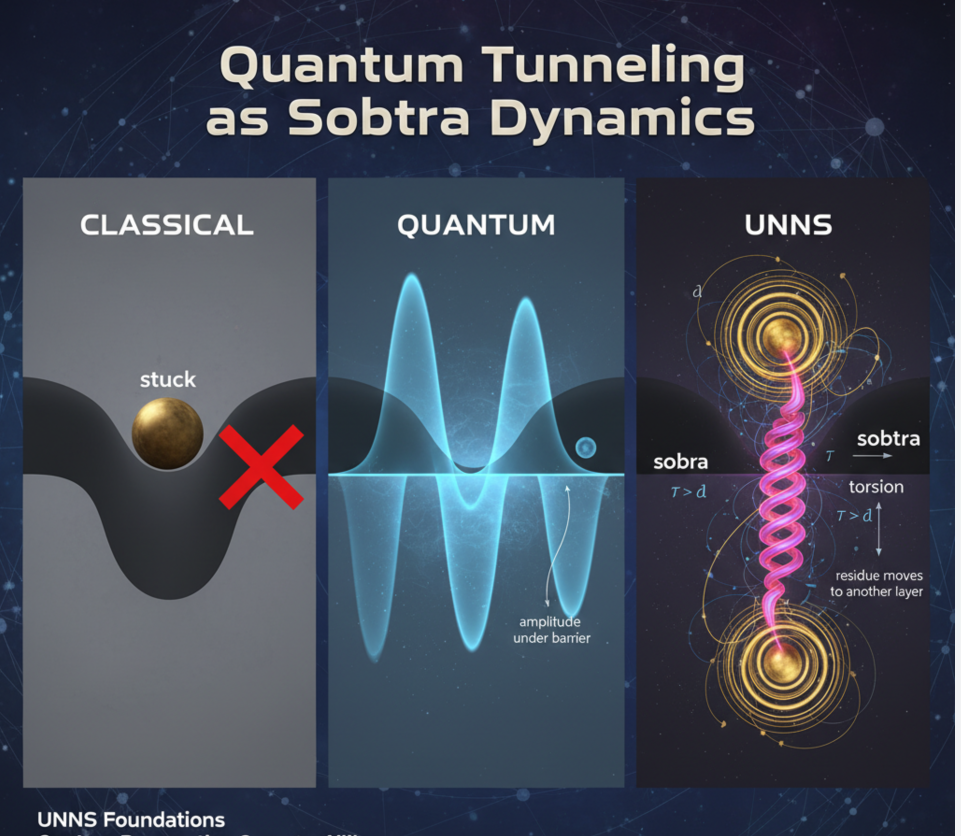

2. Three Views of the Same Barrier

The illustration below contrasts three descriptions of the same situation: classical, quantum, and UNNS.

In the classical panel the particle simply cannot cross the barrier. In the quantum panel, the wavefunction leaks through, and the particle may appear on the other side. In the UNNS panel we reinterpret this as a change of collapse channel for the residue.

3. Sobra, Sobtra, and the Barrier

In the UNNS Collapse framework, every recursive structure has a residual echo after dissipation. Operator XII decides what this echo becomes:

- sobra — the echo closes into a local remnant

- sobtra — the echo is re-opened by torsion and transported into another layer

The barrier in the tunneling picture is simply the boundary where damping (call it δ) competes with torsion (τ). Two regimes:

τ > δ → torsion wins → the residue re-opens and migrates → sobtra → tunneling (quantum-like behavior)

Classical physics can be seen as the special case where the system is effectively locked into sobra; the sobtra channel is never activated. Quantum systems live exactly at the regime where sobtra becomes possible.

4. “Negative Energy” Becomes a Torsion Layer

In standard quantum mechanics, the region inside the barrier is described as having “negative energy” relative to the particle and an exponentially decaying amplitude. You are told that the particle can never be observed in the imaginary-amplitude state, but it still contributes to the probability of crossing.

UNNS reframes this region as a torsion-active shell:

- It is not a new state of the particle, but a different configuration of the residue.

- The residue is being twisted by torsion (τ) while being damped by δ.

- If the twist accumulates faster than damping kills it (τ > δ), the residue re-appears in a displaced recursion layer: sobtra.

So the strange “negative energy region” is simply the zone where the sobtra decision is made.

5. Biological Tunneling as Sobtra Chains

In photosynthesis and quantum biology, energy moves through protein structures with extremely high efficiency. Excitons “hop” between sites that look, from a classical perspective, like they should be separated by barriers.

In the UNNS picture this is a chain of sobtra events:

- A local excitation collapses into a residue.

- Residual torsion is high (τ > δ) → sobtra is selected.

- The remnant reappears in a neighboring site / shell.

- The process repeats, forming an effective transport path.

What looks like a sequence of improbable tunneling events is, from the substrate’s perspective, a structured migration of residues across a network of layers.

6. UNNS Generalization of Tunneling

We can now line up the three views directly:

- Classical: no tunneling. The barrier is absolute. The residue is always sobra.

- Quantum: tunneling via wave amplitudes and “forbidden” regions. The mathematics knows about tails and imaginary amplitudes, but says little about what the residue is.

- UNNS: tunneling is a structured choice of collapse channel. When τ > δ, the residue becomes sobtra and shifts into a different recursion layer. The effect is observed as tunneling.

In this sense, quantum tunneling is not an exception to classical rules, but an indicator that the system is operating at a level where sobtra dynamics become unavoidable.

7. Summary

Quantum tunneling is usually presented as a phenomenon “impossible in classical physics but allowed in quantum mechanics.” UNNS reframes it as a clean structural rule inside Collapse:

- sobra — closed remnant pattern; collapse stays local.

- sobtra — torsion-reactivated remnant; collapse transitions into another layer.

- The barrier marks the competition between torsion (τ) and damping (δ).

- Tunneling occurs when Collapse picks sobtra instead of sobra.

In this way, tunneling is not an inexplicable “jump through a wall,” but the visible consequence of an invisible substrate decision about which residue channel to follow.

For the full mathematical framework behind sobra and sobtra, see the

Operator XII monograph:

Operator XII Collapse — The Completion of Recursive Grammar in the UNNS Substrate