A public, operational viewpoint: what it means to be “consistent” when a mathematical universe is not only axioms, but a running process with admissibility, curvature, and collapse.

Why this article exists

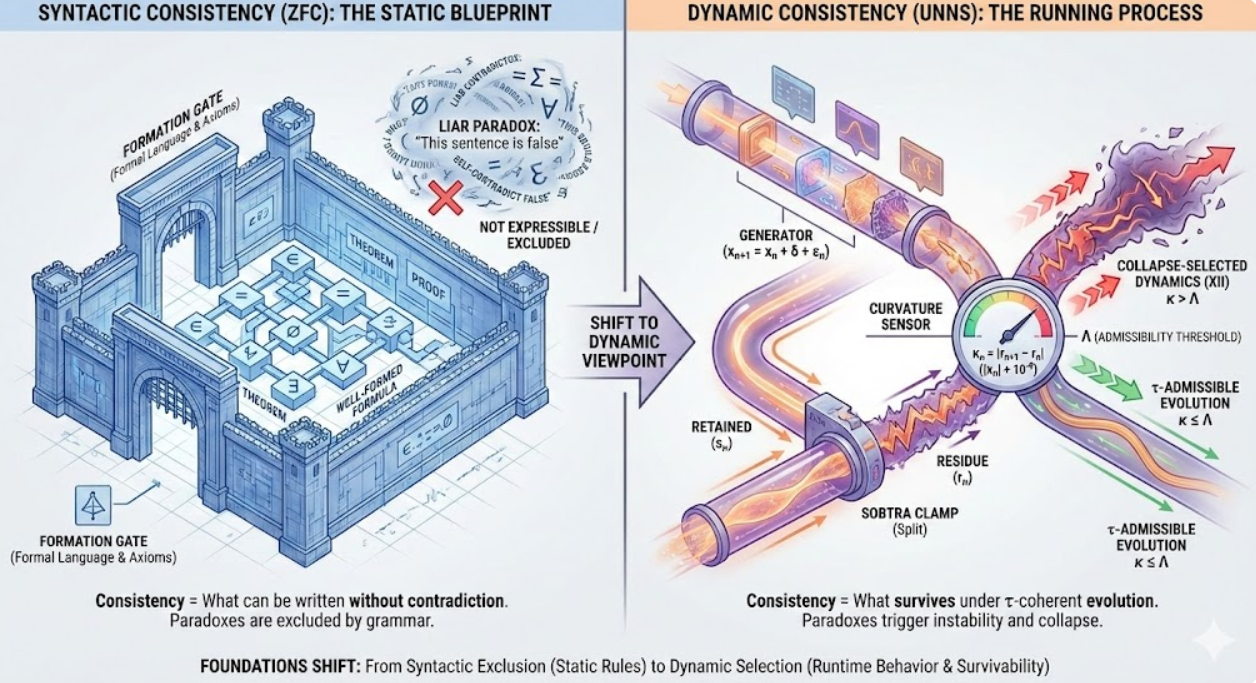

In classical set theory, “consistency” is largely a property of an axiom system and its formal language: what can be written, and what can be proved without contradiction. In UNNS, “consistency” is also a property of behavior: what survives under recursion, what remains admissible under τ-thresholds, and what collapses.

This article does not argue against ZFC. Instead, it clarifies a shift in viewpoint: syntactic exclusion versus dynamic selection. The two approaches can coexist — but they answer different questions.

Two definitions of “allowed”

- ZFC: allowed = expressible in the formal language + admitted by axioms.

- UNNS: allowed = generable + τ-admissible + stable under collapse pressure.

1) Syntactic consistency in ZFC: “What cannot be said cannot break the system”

ZFC operates inside a tightly controlled formal language: formulas are built from ∈, =, variables, logical connectives, and quantifiers. Anything that cannot be expressed in that grammar does not become a theorem, a counterexample, or a paradox — it simply does not enter the system.

What ZFC protects

Contradictions like “P and not P” from appearing as derivable statements.

How it protects

By strict formation rules (syntax) + axioms that constrain set-building.

What it does not model

The runtime of mathematical structures: stability, drift, admissibility, collapse.

In this view, liar-style constructs are not “resolved”; they are typically not expressible in the intended way inside the language. That is a design boundary: a consistency technique based on exclusion.

2) Dynamic consistency in UNNS: “A structure may exist, but it may not survive”

UNNS treats recursion as a first-class object: sequences, operator chains, and selection dynamics form a substrate in which structures can be generated and then tested. Here “consistency” becomes a question of survivability under constraints, not merely a question of formal expressibility.

Generator: xn+1 = xn + δ + εn

Sobtra clamp: sn = xn if |xn| < θ, else 0

Residue: rn = xn − sn

Curvature: κn = |rn+1 − rn| / (|xn| + 10−9)

Admissible step: κn ≤ Λ

Read this as a universal pattern, not a single model: the substrate defines (i) how states are produced, (ii) how selection splits a state into retained vs rejected content, and (iii) how a stability measure κ governs admissibility via a threshold Λ.

Dynamic consistency (UNNS) in one sentence

A system is “consistent” in an operational sense if its generated structures admit τ-coherent evolution: they remain within admissibility bounds often enough to sustain non-trivial composition, and they do so reproducibly across controlled perturbations.

3) Where paradox goes: exclusion vs collapse

Under syntactic consistency, the primary filter is “can the statement be formed and interpreted inside the language?” Under dynamic consistency, the primary filter is “does the structure remain admissible under evolution?” A liar-like loop is then reinterpreted as a high-tension recursion: it may be generable, but it tends to induce instability (κ growth) and trigger collapse selection.

Figure A. ZFC enforces consistency at the level of allowable formal expressions and derivations. UNNS enforces an additional layer: a runtime criterion of admissibility and survival under τ-thresholds and collapse (XII).

4) How κ and Λ turn “consistency” into a measurable surface

The practical advantage of a dynamic criterion is that it can be measured, exported, compared, and regression-tested. In the Chamber, κn is computed per step, Λ is adjustable, and admissibility is recomputed without rerunning the generator. This makes the τ-filter a reproducible lens rather than an interpretive slogan.

Figure B. UNNS turns “safe/unsafe” from a purely syntactic boundary into a measurable one: κn is computed from residue variation, and τ-admissibility is the inequality κn ≤ Λ. Collapse (XII) is not “a contradiction”; it is a classified regime.

Figure B (live): Regime Lens — τ-Admissibility in Action

This live figure is not a diagram. It is the same analytical instrument used in the τ-Filtered Observability Chamber, focused here on regime classification (stable ↔ transitional ↔ collapse).

Figure B (live). κ is computed per step, Λ defines τ-admissibility, and regimes emerge by classification — not interpretation. Adjust Λ to observe regime boundaries directly.

5) Mapping ZFC-style safety into UNNS-style regimes

A useful way to reconcile both viewpoints is to treat “ZFC-like behavior” as a stable subregime inside a larger space. In UNNS terms, a regime is not only a set of statements — it is a set of trajectories that stay within admissibility bounds.

Figure C. A “safe core” can be recognized as a region of high survivability under τ-filtering. UNNS adds a second axis: not only what you can describe, but what remains stable as an evolving object.

6) What this means for real mathematics and physics

The word “observability” is not decorative here. In physics, what is stable under constraints (symmetries, conservation, measurement bandwidth, noise bounds) is what becomes a reliable object of study. UNNS provides an abstract but operational way to express that pattern: stable structure is what survives under admissibility constraints.

Signal processing analogy

Sobtra acts like a threshold operator that separates retained vs rejected components, enabling an explicit residue channel for stability accounting.

Dynamical systems analogy

κ and Λ define regimes: stable, transitional, collapse-dominated. This is a phase portrait logic implemented over discrete recursion.

Foundations analogy

“Consistency” becomes two-layer: a formal language boundary (syntax) and a runtime boundary (survival under selection).

UNNS does not require you to abandon classical foundations. It gives you an additional instrument: a way to talk about when structures are not only definable, but operationally coherent under controlled stress.

7) Use the Chamber as an instrument (recommended workflow)

The τ-Filtered Observability Chamber makes these ideas concrete: it produces per-step κ profiles, admissibility masks, collapse counts, phase diagrams (Λ × δ), and multi-run comparison summaries.

Minimal workflow

- Run a deterministic simulation (seeded) to generate xn.

- Inspect κn and the admissibility barcode (κn ≤ Λ).

- Vary Λ to observe how the same underlying run moves between regimes.

- Export JSON for reproducibility and external inspection.

- Compare multiple runs to test stability of survival ratios and operator drift.

Conclusion

ZFC shows how to build a consistent universe by restricting what can be stated and how it can be derived. UNNS adds a second axis: how structures behave under recursion, selection, and admissibility constraints. Together, they offer a more complete picture of what “consistent” can mean: syntactically well-formed, and dynamically survivable.